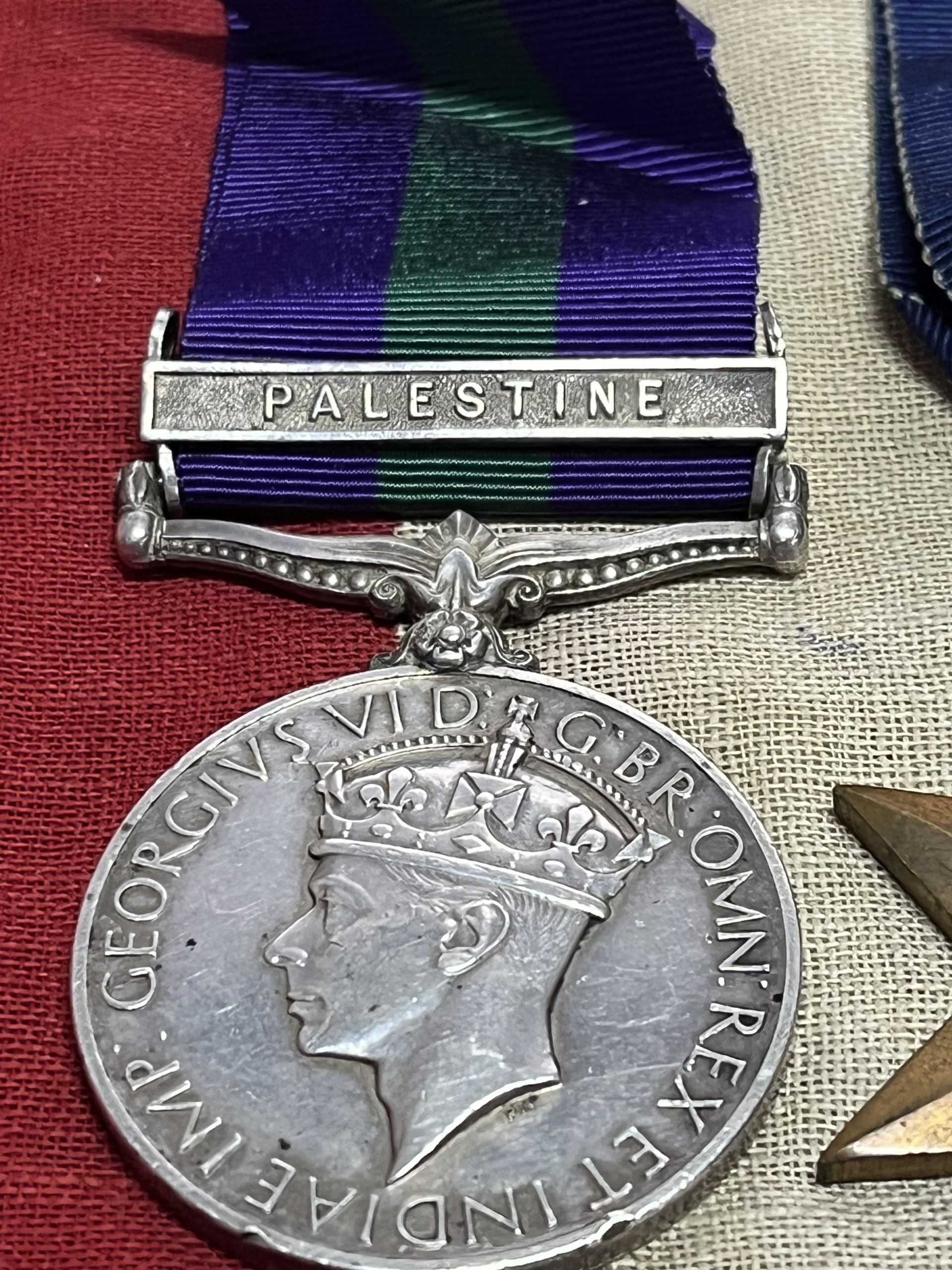

Correctly named General Service Medal: 6011384 Pte AJ Beatwell Essex R

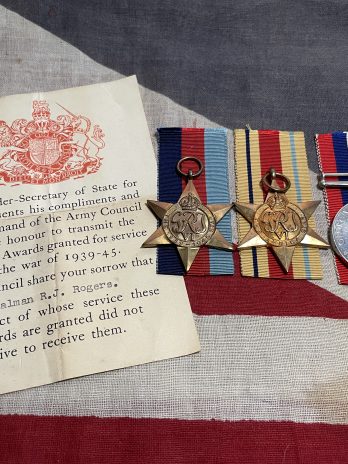

WWII medals unnamed as issued.

Alfred James was born to Daniel and Sarah in early 1917 in Ongar, Essex. They are seen to be living at 5 Willows Cottages in Chelmsford, Essex. An address used by Alfred in army documents.

Prior to enlisting in April 1935, Alfred was working as a farmer.

Enlisting into the 1st Battalion Essex Regiment, Alfred was posted to Palestine in 1936 to assist in the Arab Revolt, A popular uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine against the British administration of the Palestine Mandate, later known as The Great Revolt.

After the invasion of North Africa in 1940, Alfred has now become a member of the 8th Army whilst still with the 1st Battalion Essex Regiment.

Alfreds records confirm his capture at Masra Mutrah in Egypt. He is recorded as being in captivity from April 1942. The Battle of Matra Mutrah, an Axis victory, is dated 26th – 29th of June 1942 so evident that Alfred was captured prior to this.

Alfred finds himself imprisoned at Stalag 344 in Upper Silesia in the Czech Republic. The camp was also known as Stalag VIII-B. There from 1942, he was given the prisoner of war number 22203 and he worked as a labourer. There were many forms of work undertaken by prisoners from working on the railways to mining.

Records tell us he was held there until January 1945 when his records simply state he was ‘On March’.

The Lamsdorf Death March.

In January 1945, as the Soviet armies resumed their offensive and advanced into Germany, many of the prisoners were marched westward in groups of 200 to 300 in the so-called Death March. Some died from the bitter cold and exhaustion. The lucky ones got far enough to the west to be liberated by the American army or the Scots Guards. The unlucky ones were captured by the Soviets, who instead of turning them over quickly to the western allies, held them as virtual hostages for several more months. Many of them were finally repatriated towards the end of 1945 through the port of Odessa on the Black Sea.

Extracted from the writings of RAF Warrant Officer Joseph Fusniak, BEM who was on the march:

There was tension in Stalag 344. Rumours were circulating that the Russians were closing in; we were advised to tramp around the camp regularly and to get used to walking in case an evacuation was pending. A few days later we heard the distant rumble of artillery, causing us much anxiety and alarm. We had to wait for Red Cross parcels to be unloaded from a nearby railway station before they were distributed around the camp.

I was in the first evacuation column consisting of 4,000 PoWs and we set off shortly before dark on 2 February 1945. This was not my first time passing out through the camp gates. I reflected on two previous occasions when I had swapped identity with army colleagues in coal mine parties and managed to escape – but not for long. I was caught, beaten up at the local police station in Jaworzno and returned to the POW camp “cooler” where I spent three weeks cut off from all contact with the outside world and companions in a dark, dingy wooden box type room equipped with only a bucket for toilet deposits; no bed or mattress. One slice of bread was give to me each day with a cup of water barely sufficient to stop myself dehydrating. Hitler had ordered that further escape attempts would result in prisoners being shot after there was a mass escape attempt at Stalag Luft III.

I was in the first evacuation column consisting of 4,000 POWs and we set off shortly before dark on 2 February 1945. This was not my first time passing out through the camp gates. I reflected on two previous occasions when I had swapped identity with army colleagues in coal mine parties and managed to escape – but not for long. I was caught, beaten up at the local police station in Jaworzno and returned to the POW camp “cooler” where I spent three weeks cut off from all contact with the outside world and companions in a dark, dingy wooden box type room equipped with only a bucket for toilet deposits; no bed or mattress. One slice of bread was give to me each day with a cup of water barely sufficient to stop myself dehydrating. Hitler had ordered that further escape attempts would result in prisoners being shot after there was a mass escape attempt at Stalag Luft III. Now and then we halted for a few minutes and after 9 hours or more – well after midnight – we eventually reached a village with barns where I collapsed and crashed out for the night, sleeping in hay amongst hundreds of others. No food, lights or fires were allowed and I was physically and mentally exhausted, having covered 18-25 miles in sub-zero temperatures.

At daybreak we assembled for our second day to retreat from the advancing line of Russian artillery. People were dreadfully thirsty and sucked snow. A German NCO was sent ahead on a bicycle to arrange with the village “Burgmeister” about our intended arrival that evening and to scrounge any food that might be available, e.g. some potatoes and hot water to make weak tea. Hot water alone was always welcome as an alternative to cold when we ran out of tea. However, there were seldom facilities to boil water or even cook food except on rare occasions. A slice of bread or sausage would have to last three days. Local villagers were very poor and often were short of food themselves.

A second column of POWs apparently set off from Stalag 344 the following day. Only the disabled, those unable to walk, and some German staff and guards were left behind and later transferred by train to southern Germany. I later heard that 8,000 Russian POWs from Stalag VIII-F (located a few miles away from Stalag 344) were marched shortly after I left but were unfortunately strafed by Russian fighter planes resulting in many men killed.

Many POWs had blisters on the soles and toes of their feet that froze. In fact I found it impossible to take the shoes off my crippled feet and don’t actually remember removing them except just once in three months. Nor did I change my clothes so I must have stunk to high heaven like everyone else. Lice became an irritating nuisance and impossible to locate due to this restriction, but occasionally I found some of these 3mm long white bloodsuckers, which I crunched between my fingernails. I reckon I became infested while sleeping in a disused brick factory that we shared one night with some Russian POWs.

We reached a tavern at Ditfurt village and stopped in a barn to rest at the rear of the premises. By now the weather was not so severe and spring had arrived. Shells were falling near the river at night. The guards had seemingly abandoned us but were spotted clustered together along the riverbank through the veiled mist that lingered in the morning. A little later a firing Typhoon plane swooped down and we heard that a horse and a Yugoslavian civilian were shot in the village square. Suddenly an alarming burst of machine gun fire sounded outside the Inn and someone quickly shouted with exhilaration, “The Yanks are here!” We rushed to the barn door to greet a jeep load of GIs, except for one emotionally drained RAF colleague. Alas, he died of shock at the news never to enjoy the freedom of liberation.

After his liberation, Alfred returned home and was to marry Kathleen Lambe in 1947.

Alfred died in 2001.

All the medals have original silk ribbons.