The Tunnellers.

On the Western Front during the First World War, the military employed specialist miners to dig tunnels under no mans land. The main objective was to place mines beneath enemy defensive positions. When it was detonated, the explosion would destroy that section of the trench. The infantry would then advance towards the enemy front-line hoping to take advantage of the confusion that followed the explosion of an underground mine.

Soldiers in the trenches developed different strategies to discover enemy tunnelling. One method was to drive a stick into the ground and hold the other end between the teeth and feel any underground vibrations. Another one involved sinking a water-filled oil drum into the floor of the trench. The soldiers then took it in turns to lower an ear into the water to listen for any noise being made by tunnellers.

It could take as long as a year to dig a tunnel and place a mine. As well as digging their own tunnels, the miners had to listen out for enemy tunnellers. On occasions miners accidentally dug into the opposing side’s tunnel and an underground fight took place. When an enemy’s tunnel was found it was usually destroyed by placing an explosive charge inside.

Mines became larger and larger. At the beginning of the Somme offensive, the British denoted two mines that contained 24 tons of explosives. Another 91,111 lb. mine at Spanbroekmolen created a hole that afterwards measured 430 ft. from rim to rim. Now known as the Pool of Peace, it is large enough to house a 40 ft. deep lake.

In January, 1917, General Sir Herbert Plumer, gave orders for 20 mines to be placed under German lines at Messines. Over the next five months more than 8,000 metres of tunnel were dug and 600 tons of explosive were placed in position. Simultaneous explosion of the mines took place at 3.10 on 7th June. The blast killed an estimated 10,000 soldiers and was so loud it was heard in London, gave orders for 20 mines to be placed under German lines at Messines. Over the next five months more than 8,000 metres of tunnel were dug and 600 tons of explosive were placed in position. Simultaneous explosion of the mines took place at 3.10 on 7th June. The blast killed an estimated 10,000 soldiers and was so loud it was heard in London.

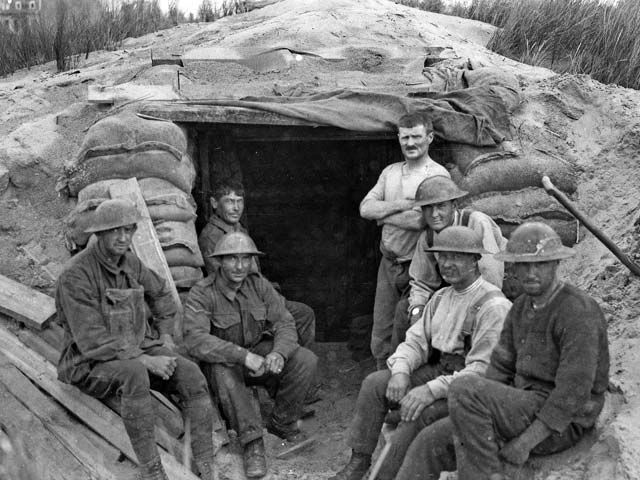

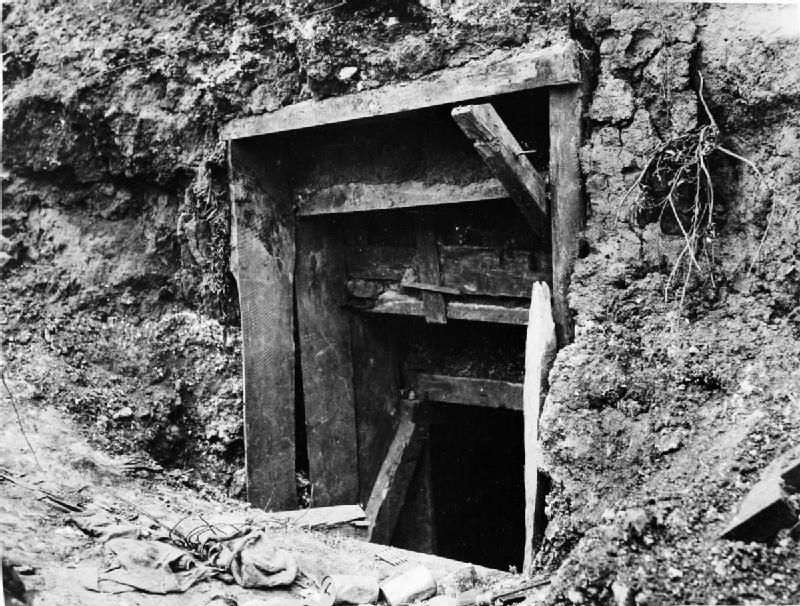

Whole volumes have been written on the work of the Tunnelling Companies, but a quick overview of a mining operation is as follows. A deep shaft would first be sunk in the friendly trenches, with a ‘shaft house’ at the entrance for the air pump etc. Narrow tunnels (known as galleries) were then driven underground towards the enemy line. The work was complicated by the fact that it had to be done as silently as possible, as the enemy miners were driving their own galleries in the opposite direction, and each side would be listening out for any sound made whilst working. Once under the enemy position, a mine chamber would be dug out and packed with explosives, which would be fired electrically at a key moment, usually a series of them at the start of a major offensive.

There were obviously huge dangers involved for the men working below ground. These ranged from the natural – such as collapses and carbon monoxide build-up – through to viscous combat with enemy tunnellers. If the other side heard you digging nearby, they might set an explosive charge, called a camouflet, in their own tunnel and set it off to kill or trap you underground. One side might also break into the other’s tunnel system and brutal, often hand-to-hand, fighting would ensue, which again would end with charges being set off to wreck the earthworks and kill or trap the enemy miners.

Towards the end of the war, as action became more mobile and less trench-bound in 1918, the Tunnelling Companies moved on to yet more dangerous work above ground, dealing with booby-traps and unexploded shells, including gas. I think, then, it is the sheer amount of danger that they faced that would earn a man involved in tunnelling great respect from those who understood what his work entailed.