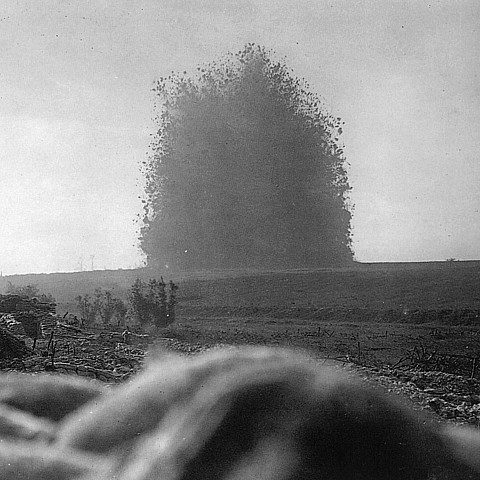

WW1’s Biggest Blast.

A blast that obliterated 10,000 Germans.

When the British detonated 19 mines at Messines on 7 June 1917, it was the biggest man-made explosion ever seen.

In the minutes before 3.10am – Zero Hour on Zero Day – silence descended for the first time in weeks over Messines. The ridge lay at the southern end of the Ypres battlefield on the Western Front and had been a German stronghold since 1914. Taking it was seen as a vital preliminary to the Battle of Passchendaele, which followed a month later.

But as Sgt-Maj Douglas Pegler had observed in April 1916: “Messines is one of the strongest points in the German line. I should think the only way to capture it would be to surround it and starve it.”

Forty-five minutes before Zero Hour, Captain Oliver Woodward, an Australian tunneller, made the final preparations for an alternative, more explosive solution. For weeks, more than 2,000 guns and howitzers had been bombarding the German trenches with 3.5 million shells. As British troops withdrew after midnight and Zero Hour ticked nearer, little did those enemy combatants know that the greatest danger lay beneath their feet.

“At 2.25am, I made the last resistance test and then made the final connection for firing the mines,” Woodward wrote. “This was rather a nerve-racking task as one began to feel the strain, and wonder whether the leads were properly connected up… breathlessly we watched the minute hand crawl towards the 10 minutes, then, with white faces, we strained our eyes towards the enemy line, which had become visible in the grey dawn.”

The wires led through soil and clay to 21 mines that had been buried in an ambitious operation that had taken months – directed, like the Battle of Messines it triggered, by General Herbert Plumer. The explosives contained ammonal, a potent mixture of ammonium nitrate and aluminium powder, and weighed more than 400 tons (the biggest single mine weighed 41 tons, more than the heaviest tanks used in the war).

“I do not know whether or not we shall change history tomorrow,” Major-General Charles Harington, chief of staff of the British Second Army, said the day before, “but we shall certainly alter geography.”

“Three minutes to go.” Woodward recalled the countdown. While he and his fellow miners waited to see if their wiring would function, more than 80,000 infantrymen prepared to attack and bombard the ridge. The explosion would be their signal to advance. “Two to go – one to go – 45 seconds to go – 20 seconds to go – and then 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, – FIRE!!”

For the following 19 seconds, Flanders shook in what would remain the largest man-made explosion until the birth of the nuclear bomb. Only two mines failed to explode. The book Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers’ War recounts how Field Marshal Haig had invited journalists to watch from the safety of nearby Kemmel Hill.

Meanwhile, according to press reports, Lloyd George, the Prime Minister, was among those who heard the explosions in London. Later that morning, scientists arriving at the labs at Lille University would mistake them for an earthquake.

“Our trench rocked like a ship in a strong sea and it seemed as if the very earth had been rent asunder,” Private Albert Johnson, one of the infantrymen, recalled. “What the Germans thought of this is better described without words.” Witnesses reported seeing clods the size of houses hurtling through the debris. When the earth settled, the “diameter of complete obliteration” was, on average, twice that of the blast craters themselves, the largest of which measured 80m wide and 15m deep.

One British lieutenant reported finding in one crater no human remains larger than a single foot encased in its boot. “I saw a man flung out from behind a huge block of debris silhouetted against the sheet of flame,” Lieutenant AG May of the Machine Gun Corps wrote. “Presumably some poor devil of a Boche. It was awful; a sort of inferno.”

The blast also shocked and concussed hundreds of the British troops waiting to go over the top. Allied losses in the ensuing week of fighting would be heavy, if fewer than those sustained by German troops. Estimates of the number of Germans killed in and after the explosions have been as high as 25,000, with up to 10,000 dying instantly.

The Battle of Messines lasted for seven days, until 14 June, less than a month before the even larger and bloodier Passchendaele campaign. It would be considered a success for the British, if a costly one. The German general Hermann von Kuhl called it one of the great tragedies of the war.

Lloyd George was triumphant even with the benefit of years of reflection. In his 1934 war memoirs, he wrote: “The capture of the Messines Ridge, a perfect attack in its way, was just a useful little preliminary to the real campaign, an aperitif provided by General Plumer to stimulate the public appetite for the great carousal of victory which was being provided for us by GHQ.”

Extracted from The Independant