Britains WW1 Pacifist Hero. Lance Corporal William Harold Coltman.

He went out alone to rescue wounded men who had been left behind when their comrades were forced to retreat from the German army…

There was nothing they could do.

Wounded soldiers cried out for help as they lay scattered beneath Mannequin Hill. But with enemy machine gun and shell fire raining down from above, their pals in the 1st/6th North Staffordshire Regiment had no choice but to abandon them – or face annihilation.

Reluctantly, prompted by their officers, the unharmed soldiers and walking wounded withdrew from the ferocity of the enemy attack, leaving a handful of their mates behind. These were men who were too badly wounded to walk or even crawl away from the enemy guns. But the German fire raining from above meant that any rescue attempt would sacrifice more lives.

It was just a few days after the North Staffords’ glorious victory at the St Quentin Canal. In comparison, the follow up assault on the Beaurevoir-Fonsomme Line, known as the Battle of Ramicourt, was expected to be easy.

It was anything but. German infantry put up a surprisingly stubborn line of resistance. Machine gunners had fired at the advancing North Staffords from a series of sunken lanes and individually dug rifle pits, or from well constructed concrete shelters.

Yet, the North Staffords had reached the Beaurevoir-Fonsomme Line, which was effectively a support trench for the Hindenburg Line, and their bayonets had been bloodied in the charge. They had captured all their objectives.

But heavy fire was poured on the North Staffords by enemy soldiers above them on Mannequin Hill. At risk of being cut-off and surrounded by an enemy counter-attack, officers had no option but to order the men to retreat – and the weight of enemy fire meant there was no choice but to leave a few scattered wounded behind.

But then a pacifist heard there were still wounded out in the valley beneath the hill and ventured out alone to try to save as many as he possibly could.

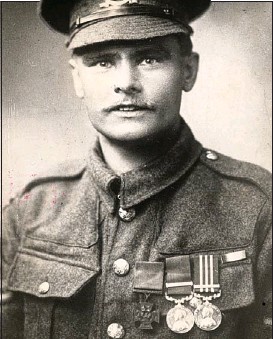

His name was Lance Corporal William Harold Coltman, a deeply religious man who became the most decorated soldier in the British Army, during the Great War, without firing his rifle.

His Christian faith meant he would not kill – and there were many men who shared his pacifist beliefs languishing in prison cells and even facing the threat of execution.

But Coltman, from Winshill, near Burton, had joined the army as a 23-year-old rifleman with the 1st/6th North Staffords in January, 1915. However, he vowed never again to shoulder a rifle, after spending a night trapped under heavy fire in a foxhole listening to the cries of wounded soldiers. The next morning, he submitted a request to retrain as a stretcher bearer.

If any of his comrades mocked his decision to set aside his rifle, they were soon silenced by his quiet bravery. Coltman was fearless and determined under fire when tasked with rescuing the wounded.

He had already been mentioned in dispatches and awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French Army when he won the Military Medal (MM), in February 1917, for rescuing an officer who had been wounded in the thigh, from no man’s land, while under fire.

He won a bar to his MM – effectively a second MM – for his conduct over a few days in June, 1917. He had taken command to limit damage when an ammunition dump had been hit by mortar fire, then he bandaged up wounded men when battalion headquarters were shelled, and finally organised a rescue party to save men trapped in a collapsed trench tunnel.

In July, 1917, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for searching for wounded soldiers under shell and machine gun fire throughout a long night, when his, ‘absolute indifference to danger had a most inspiring effect upon the rest of the men’.

Then on September 28, 1918 – the day the 1st/6th North Staffords captured the Riqueval Bridge, the single most decisive action in the Battle of the St Quentin Canal – Coltman had received a bar to his DCM for tending to wounded men under artillery fire and carrying them to safety. According to his citation, Coltman, ‘remained at his work without rest or sleep, taking no heed of either shell or machine-gun fire, and never rested until he was positive that our sector was clear of wounded’, setting the ‘highest example of fearlessness and devotion to duty’.

Just a few days later, on October 3, Coltman heard from the retreating North Staffords that wounded men had been left behind. So he set out, alone, back along the valley in front of Manniquin Hill in search of those unfortunate soldiers.

The German army still occupied the high ground, the threat from heavy artillery and machine gun fire remained – but Coltman made his way towards the gunfire, zeroing in on the cries of the nearest wounded soldier.

This man had no doubt seen his comrades withdraw. He would have known his wounds were serious, perhaps fatal, and would have been in agonising pain. Perhaps he had given up all hope of survival.

Then suddenly, from nowhere Coltman was alongside, pulling out his first aid pack and patching up his wounds the best he could. Coltman then hauled the wounded soldier onto his back and carried him back to the British lines.

Handing this man over to other stretcher bearers to carry to the nearest aid station, Coltman went back, into the face of machine gun and shellfire once more, he searched the valley until he found another injured soldier and carried him back. He then went out again, and once more returned with another crippled infantryman.

For 48-hours he kept up his efforts, until finally, exhausted, he lay down to rest.

For his bravery, Coltman was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest honour the British Army can bestow.

Recommending Coltman receive the VC, his commanding officer, Major Charles Child Dowding wrote: “Hearing that there were wounded in front who had not been attended to owing to the heavy concentrated enemy artillery and machine gun fire, this very gallant non-commissioned officer, on his own initiative, went forward alone into the valley of the hill, in the face of fierce enfilade fire, found the wounded, dressed them, and carried each one to his stretcher squad in rear of our line, thus saving their lives.

“In that action alone, this very gallant non-commissioned officer dressed and carried wounded for 48-hours without rest; his efforts did not cease until the last wounded man had been attended to.”

One of those men rescued by Coltman may have been Private Frederick John Clarke, of Burslem, a shop assistant before the war, who had joined the army in 1916 at the age of 19.

His military record shows he was with the 1st/6th North Staffords and was shot in the foot and the stomach in the attack of October 3. With wounds like that, he could have easily been one of the men left behind and rescued by Coltman that day.

Private Clarke was shipped out of France and treated at the 1st Birmingham War Hospital, which was set up in the former Rubery Asylum. He later became manager of the Boyce Adams store in Fenton.

But there were many men who Coltman couldn’t save, whose names have been researched by historian Richard Ellis, of Dresden.

One of these men was Lance Corporal Arthur Brocklehurst, a 29-year-old miner, who was married to Jessie Brocklehurst (nee Wooliscroft), of 2 Dresden Street, Hanley. At his least his widow had the small comfort of receiving the Military Medal her husband was awarded, posthumously. He is buried in Montbrehain British Cemetery, Aisne, France close to where he fell.

Private John William Smart was another MM winner who died on October 3. The son of Joseph and Hannah Smart, of 10 Marsh Street, Longton, he described himself as an ‘out of work collier’ when he enlisted one month after his 18th birthday, on December 8, 1915. He also received his medal posthumously. He is buried in Levergies Communal Cemetery.

Private George William Bradshaw, of 48 St Mark Street, Shelton, fought in the Battle of Loos and the Battle of the Somme with the 1st/5th North Staffords, the Potteries battalion, before that was disbanded in 1918 and he joined the 1st/6th. He was mortally wounded in the attack and died on October 4, at the age of 39. He rests at Tincourt New British Cemetery.

Private Enoch Hawley was the son of Thomas Hawley, of 65 Alexandra Rd, Normacot. He was aged 30 when he died and has no known grave, but is remembered on the Vis-En-Artois Memorial.

The attack of October 3, 1918 was the last major battle the 1st/6th North Staffords took part in. Just over a month later, the war ended.

As for William Coltman, he returned home to a hero’s welcome – which the modest medic avoided by getting off the train in the Potteries, and walking 20 miles home to dodge the crowd waiting to cheer him at Burton station.

He was however given full honours when he was invited to Buckingham Palace to receive his Victoria Cross from King George V.

After returning home and settling back into every day life, Coltman took a job as a grounds keeper with the town’s Parks Department.

During the Second World War he commanded the Burton-on-Trent Army Cadet Force with the rank of Captain.

He retired from his job in 1963 and died at Outwoods Hospital in Burton-on-Trent in 1974 aged 82.

He was a regular at the North Staffordshire Regiment reunions, often held at Cobridge TA Centre in Stoke-on-Trent.

The late Sentinel correspondent John Abberley met Coltman at a tribute to a fellow VC winner, Jack Baskeyfield of Burslem. John described him as, ‘a bespectacled gentleman who didn’t look as if he’d hurt a fly’, adding: “Coltman sat quietly. Apart from his red ribbon of valour, the lion-hearted hero was hardly noticed in the crowd.”

Coltman’s medals, including his Victoria Cross, are on display at the Staffordshire Regiment Museum at Whittington, and the Coltman VC trench attraction is named in his honour.

William Coltman Way, in Tunstall, also bears his name, as does the Coltman VC Peace Wood, in Winshill.