A Brief History Of Camouflage.

Camouflage in nature

Any history of camouflage must properly start with ‘mother nature’. From wood ants to pufferfish and octopi to birds, a wide array of animals conceal themselves – sometimes amazingly from predators with camouflage.

Two British zoologists and an American painter played key roles in translating camouflage in nature into techniques humans could put to military use. One of those zoologists, Sir Edward Poulton, wrote the first book on camouflage in 1890 (The Colours of Animals). An early adherent of Darwinism, Poulton believed that animal mimicry (imitation) for concealment was proof of natural selection.

The American painter Abbott Thayer popularised two particular concepts of camouflage: countershading explains the lighter underbellies common to many animals – this cancels out shadowing from the overhead sun, giving the animal a flat, two-dimensional appearance. Disruptive coloration, meanwhile, refers to ‘splotchiness’ in an animal’s colouring; this visual effect helps to obscure the contours of its body.

Thayer suffered from bipolar disorder and panic attacks – conditions not helped by public criticism of his controversial theories, which gained prominence in the lead-up to the First World War. Thayer defended those theories stoutly until his death in 1921.

In 1940, zoologist Hugh Cott built on Poulton’s more scientific concepts with ideas of his own, including contour obliteration – basically, making it difficult to perceive a continuous form by blurring its defining edges – and shadow elimination – as the name suggests, reducing the appearance of telltale shadows.

Military khaki

Prior to the invention of the modern rifle in the mid-1800s (the earliest rifles were in use during the 15th century), militaries the world over clad their soldiers in bright shades of colour – consider, for example, British troops in their iconic madder red uniforms (red coats).

But marksmen began wearing more inconspicuous garb to conceal themselves while picking off targets. Austrian Jägers (meaning ‘hunters’) wore light grey, while the British 95th Rifle Regiment wore dun green.

Military khaki (the term derives from the Urdu and Persian words for ‘dust’) arose in the mid-19th century, as soldiers in the British Indian Army began dyeing their white uniforms with tea and curry. Not only did khaki end the hopeless struggle to keep one’s uniform spanking white, it also reduced soldiers’ visibility from a distance.

Despite this, brighter military garb tended to dominate until the early 20th century. Why were militaries so reluctant to adopt darker uniforms? The answer lay in the evolving nature of warfare: in addition to practical considerations like durability and visibility, uniforms performed a psychological function of making soldiers feel battle-ready. Orderly lines of brightly clad soldiers marching in formation – a key feature of musket-driven warfare – gave way to guerrilla warfare. To fight and win in this new era, stealth was a core advantage.

The First World War

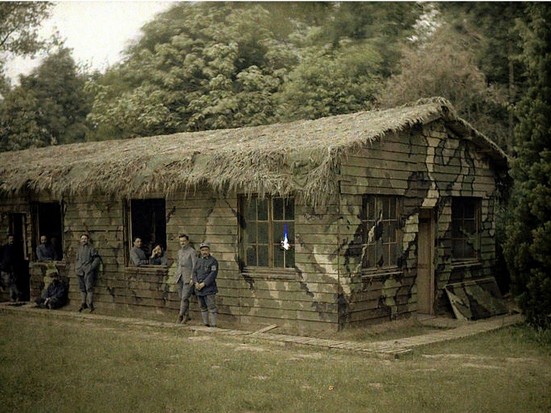

A new threat darkened the horizon in the run-up to the First World War: enemy aerial reconnaissance. (Aerial attack became possible somewhat later.) As such, militaries first used camouflage patterning and tactics to hide, not people, but locations and equipment.

The French organised the first units of camoufleurs – specialists in camouflage – in around 1914. Initial tactics were confined to painting vehicles and weaponry in disruptive patterns to blend into the surrounding landscape. Camoufleurs were both practitioners and teachers of their peculiar art. They taught other military units how to disguise their equipment with paint, to toss netting interwoven with fake leaves over a shed stocked with materiél (military equipment) and to erase any telltale truck tracks and cannon blast marks.

The term ‘camouflage’ itself dates to a practical joke from 16th-century France. The prankster would fashion a camouflet – a hollow paper cone, lit to smoulder at one end – and stick it under an unfortunate sleeper’s nose. The sleeper would jolt rudely awake at the first lungful of smoke.

Camouflet later referred to a lethal powder charge that could entrap a tunnelling enemy troop underground – a more deadly trick. To complete this layered etymology, the French verb camoufler means, appropriately, ‘to make oneself up for the stage’.

Camouflage goes baroque

Camouflage techniques grew increasingly detailed as the First World War progressed, and fascination with camouflage – in popular as well as military circles – grew. Factories cranked out pâpier-maché heads by the thousands; mounted on sticks – soldiers might poke these decoys above the trench line, tempting the enemy out of his safe foxhole to fire. False trees were equally popular: regiments would sneak onto the battlefield unseen at night, fell an actual tree, then replace it with a hollowed-out replica with a soldier hidden inside.

Camouflage spread to the seas, too. In 1917, British lieutenant Norman Wilkinson introduced the concept of ‘dazzle’-painting warships to curb losses: mostly black-and-white-zigzagged ‘dazzle’ paint was supposed to throw off the enemy’s calculations of a ship’s size, speed and distance, making an accurate hit more difficult. German U-boats sank 23 British ships weekly that year, 55 in one week of April 1917 alone. ‘Dazzle-mania’ subsequently spread among Allied navies, although its actual effectiveness was never proven.

The Second World War

As mentioned above, evidence that camouflage actually worked was patchy. However, as the world marched towards the Second World War, the fresh threat of aerial attack prompted militaries on both sides to use camouflage more widely. With the exception of dazzle, all First World War-era camouflage tactics were revived and expanded. Military literature of the period is awash with camouflage training manuals aimed at every soldier, from callow privates to top brass.

Two Allied wins during the Second World War owed their success largely to camouflage: El Alamein in 1942, and D-Day in 1944. During the second battle of El Alamein, the Allies blocked the Germans from seizing the Suez Canal with a mind-bogglingly detailed camouflage-plan involving inflatable tanks, fake artillery blasts and – extraordinarily – hiding the entire Suez Canal from aerial view. This was the masterwork of British camoufleur and stage magician Jasper Maskelyne. Prior to D-Day, the Allies staged a false build-up of troops in Scotland and Kent, while hiding their true efforts to amass troops to storm Normandy. The ruse continued once they landed in France with the ‘Ghost Army’ – a sham-army standing in for the actual US battalion rushing the Normandy beaches

Extracted from History Extra